Colonial Architecture Destinations USA: A Definitive Guide to Historic Styles

The architectural fabric of the United States is an intricate palimpsest, reflecting the varied ambitions, climates, and material constraints of European powers during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. To engage with the most significant historical sites is to move beyond mere aesthetic appreciation; it is to investigate the structural manifestations of colonial governance and cultural transplantation. These structures were not merely shelters but statements of permanence in a landscape that the settlers perceived as both a vacuum and a threat.

While contemporary architectural discourse often homogenizes “Colonial” as a single aesthetic of white siding and symmetrical windows, a deeper analysis reveals a highly fragmented reality. The steep-pitched saltboxes of New England, the thick-walled adobe missions of the Southwest, and the galleried townhouses of the French Quarter represent radically different responses to the American environment. Exploring these locations requires an understanding of how timber, stone, and brick were mobilized to recreate European hierarchies in a “New World.“

This reference work deconstructs the premier historical landscapes of the nation. We will examine the architectural logic that governs these destinations, the systemic pressures that have preserved or altered them, and the logistical frameworks required for modern travelers and scholars to navigate them effectively. By treating these sites as living records rather than static museums, we provide the clarity necessary to understand the enduring influence of the pre-Revolutionary built environment.

Understanding “colonial architecture destinations usa”

When we discuss colonial architecture destinations usa, we are referencing a specific set of geographical hubs where the pre-1776 built environment remains dominant or meticulously preserved. However, the term is frequently oversimplified. To the casual observer, it might suggest only the British influence in the original thirteen colonies. To the architectural historian, it encompasses a continental expanse where Spanish, French, and Dutch footprints are equally vital to the narrative of North American development.

The Complexity of Authenticity

One of the primary risks in identifying these destinations is the conflation of “historic” with “reconstructed.” A site like Williamsburg, Virginia, represents a fascinating intersection of 18th-century survival and 20th-century interpretation. Understanding the delta between an original structure and a colonial revival reconstruction is essential for a high-fidelity experience. The “best” destinations are often those where the layering of history is visible—where a Georgian brick facade sits atop a much older fieldstone foundation, revealing the evolution of wealth and local industry.

Multi-Perspective Definitions

These destinations must be viewed through three distinct lenses:

-

Materiality: How did local limestone, oyster-shell tabby, or old-growth timber dictate the height and durability of the structures?

-

Socio-Political Hierarchy: How did the design of a Virginia plantation house versus a Massachusetts meeting house reflect the different governing philosophies of their respective colonies?

-

Climatic Adaptation: Why did the Spanish in St. Augustine favor thick coquina walls while the French in Louisiana favored raised basements and wide porches (galeries)?

Deep Contextual Background: The Historical Evolution

Colonial architecture in America was never a static import; it was a series of improvisations. In the early 17th century, settlers lacked the specialized tools and labor forces required for the grand stonework of Europe. This led to a “frontier functionalism” that eventually matured into the sophisticated Georgian and Federal styles we recognize today.

The British Atlantic World

In the North, the English utilized the vast forests of New England to develop heavy timber-frame construction. The “Saltbox” shape emerged not from a whim, but as a practical way to expand a home under a single sloping roofline to accommodate growing families while shedding heavy snow. In the Mid-Atlantic, the presence of skilled bricklayers and the availability of clay led to the rise of the quintessential red-brick Philadelphia rowhouse, a model of urban efficiency that pre-dated the Industrial Revolution.

The Spanish and French Fringe

While the British moved westward from the Atlantic, the Spanish moved northward from Mexico and Florida. Their architecture was defensive and ecclesiastical. The thick-walled “Mission” style was designed for thermal mass—keeping interiors cool during the day and radiating heat at night. Simultaneously, in the Mississippi Valley, the French developed the “Poteaux-en-Terre” (posts-in-earth) method, which eventually evolved into the sophisticated Caribbean-influenced architecture of New Orleans, designed specifically to withstand high humidity and frequent flooding.

Conceptual Frameworks and Mental Models

To analyze a historic destination effectively, it helps to employ specific mental models that go beyond the visual surface.

1. The Vernacular vs. Academic Model

Most early colonial buildings are “vernacular”—built by laypeople using local traditions. As the colonies grew wealthy, they adopted “academic” styles, like Georgian, which relied on pattern books and classical proportions (the Golden Ratio). Distinguishing between these two reveals the economic maturity of a destination.

2. The Path of Material Resilience

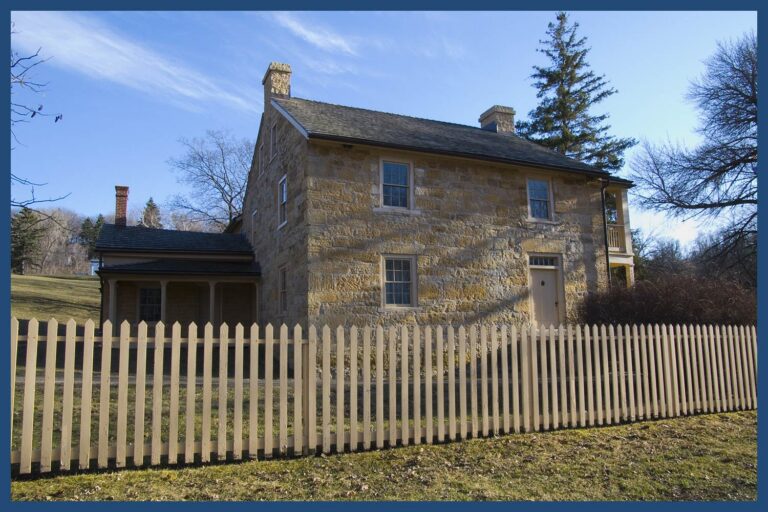

This model tracks the transition from ephemeral materials (thatch and wattle) to permanent ones (brick and stone). A destination that preserves the transition—such as the stone houses of the Hudson Valley—reveals the systemic stabilization of that community.

3. The Climatic Response Framework

This mental model asks: “How does this building breathe?” In the South, the answer is “high ceilings and cross-ventilation.” In the North, the answer is “low ceilings and a central chimney stack.” This framework explains why New England colonial styles look fundamentally out of place when transplanted to the Sun Belt.

Key Categories and Regional Variations

The diversity of destinations can be categorized by the colonial power and the resulting architectural DNA.

| Region | Primary Style | Key Material | Distinguishing Feature |

| New England | Post-Medieval/Saltbox | Timber/Siding | Central chimney, steep gables |

| Mid-Atlantic | Dutch Colonial | Brick/Stone | Gambrel roofs, flared eaves |

| The Chesapeake | Georgian Colonial | Brick | Symmetry, formal entryways |

| Deep South | French Colonial | Tabby/Timber | Raised basements, wide porches |

| Southwest | Spanish Mission | Adobe/Stucco | Bell towers, internal courtyards |

| Florida | Spanish Colonial | Coquina Stone | Loggias, high-walled gardens |

Decision Logic: Authentic Survival vs. Curated Narrative

Travelers must decide between “Organic Survival” sites (like Marblehead, MA), where buildings are lived in and modified, and “Museum Narrative” sites (like Old Salem, NC), which are curated for educational impact. The trade-off is between the grit of lived-in history and the clarity of a restored timeline.

Detailed Real-World Scenarios

Scenario 1: The New England Seaport (Newport, RI)

Newport offers one of the highest densities of original colonial structures.

-

The Constraint: High coastal salt exposure leads to rapid wood rot.

-

The Choice: Extensive use of modern epoxy resins for structural stabilization versus traditional timber replacement.

-

Failure Mode: If a preservationist uses modern non-breathable paint, moisture becomes trapped in the 300-year-old oak, causing catastrophic interior decay.

Scenario 2: The Adobe Mission (Santa Fe, NM)

Santa Fe represents the Spanish Colonial identity through the “Pueblo Deco” and original Mission forms.

-

The Constraint: Adobe is effectively sun-dried mud; it dissolves without constant maintenance.

-

The Technical Requirement: Annual “mudding” or the controversial use of cement-based stucco.

-

Second-Order Effect: Cement stucco protects the walls but prevents the building from “breathing,” often leading to structural “sweating” and the collapse of the interior adobe core.

Planning, Cost, and Resource Dynamics

Visiting or studying these sites involves a significant allocation of resources. The “cost” is not just financial but also the “temporal investment” required to reach remote locations like St. Augustine or certain upstate New York Dutch settlements.

Direct and Indirect Costs

| Resource | Value Range | Variability Factor |

| Entry Fees (Museum Sites) | $20 – $60 | Private vs. State-run |

| Specialist Tours | $100 – $300 | Architectural depth vs. General history |

| Opportunity Cost | High | Travel time to non-urban historic hubs |

| Local Lodging (Historic) | $250 – $600 | Stay in an original 1700s inn |

Tools, Strategies, and Support Systems

For those seriously engaging with these sites, certain tools enhance the analytical depth of the visit.

-

Dendrochronology Reports: Using tree-ring data to verify the exact year a beam was felled. Many museum sites now provide these.

-

Infrared Thermography: Used by professionals to see through plaster walls to identify original post-and-beam structures without destructive testing.

-

HABS/HAER Archives: The Historic American Buildings Survey provides detailed blueprints of almost every major colonial site, accessible for free online.

-

GIS Mapping: Mapping the relationship between colonial town centers and their proximity to original water sources and timber stands.

-

Color Stratigraphy: A strategy used by restorers to peel back layers of paint to find the original 18th-century pigment.

-

Heritage Seeds/Gardening: Understanding the flora of the destination to see how it integrated with the kitchen gardens of the era.

Risk Landscape and Taxonomy of Failure

Preserving colonial architecture is a battle against entropy. The risks are often compounding.

-

Gentrificaton-Induced Alteration: High property values in historic towns lead to “gut renovations” where interior historic fabric is destroyed to create “open-concept” floor plans, effectively killing the building’s historical integrity.

-

Material Incompatibility: Using modern Portland cement to re-point 18th-century brickwork. Because modern cement is harder than old brick, it causes the brick to “spall” (shatter) during freeze-thaw cycles.

-

Climate Change Volatility: Many colonial hubs (Charleston, Annapolis, St. Augustine) are coastal. Rising sea levels pose an existential threat to foundations built when the water line was significantly lower.

Governance, Maintenance, and Long-Term Adaptation

The survival of these destinations depends on “Preservation Governance”—the local boards and laws that prevent the demolition of the past.

Layered Maintenance Checklist

-

Daily/Weekly: Monitoring for moisture intrusion—the primary killer of timber-frame houses.

-

Seasonal: Inspection of “sacrificial” layers (paint and lime wash) designed to wear away so the structural wood/stone doesn’t.

-

Decadal: Re-evaluation of structural settle and foundation integrity.

Adjustment Triggers

If a historic district sees more than a 15% increase in “teardowns” of non-protected adjacent properties, the “historic character” risk has been triggered, often leading to the loss of UNESCO or National Landmark status.

Measurement, Tracking, and Evaluation

How do we measure the “success” of a colonial destination?

-

Leading Indicators: The presence of specialized tradespeople (blacksmiths, lime-burners) in the region. If the skill-base dies, the buildings follow.

-

Lagging Indicators: Property value premiums for “Certified Historic” status.

-

Qualitative Signals: The “Sense of Place”—the degree to which the modern sounds and sights of the 21st century have been mitigated to allow the architecture to speak.

Documentation Examples

-

Easement Records: Legal documents that “lock” the facade of a building against future changes.

-

Structural Monitoring Logs: Tracking how an adobe wall moves over a century.

Common Misconceptions and Oversimplifications

-

Myth: All colonial houses were white.

-

Correction: Pigments like Prussian Blue and Barn Red were common. White became a standard only during the Colonial Revival movement of the 1920s.

-

-

Myth: “Log cabins” are the quintessential colonial house.

-

Correction: Log construction was a Swedish/German import and was rarely used by English settlers in the primary Atlantic settlements until much later.

-

-

Myth: Colonial buildings are “primitive.”

-

Correction: The joinery and engineering required to keep a massive timber frame standing for 350 years is a level of craftsmanship rarely matched in modern residential construction.

-

Ethical and Contextual Considerations

We cannot discuss colonial architecture destinations usa without addressing the labor that built them. The exquisite brickwork of the South and the timber-clearing of the North were frequently the products of enslaved labor or indentured servitude.

A modern, authoritative destination does not shy away from this. It integrates the architecture of the “dependency” (slave quarters, kitchens) into the primary tour. The ethics of preservation today require us to maintain the entire footprint of the site, not just the “Big House.” Failure to do so results in a sanitized, inaccurate representation of history that erodes the site’s authority over time.

Conclusion

The study of colonial architecture in the United States offers a profound window into the systemic roots of the American identity. These structures serve as more than mere tourist destinations; they are the physical manifestation of European-indigenous collisions, climatic adaptations, and the evolution of American labor.