Victorian Home Restoration Destinations USA: The 2026 Definitive Guide

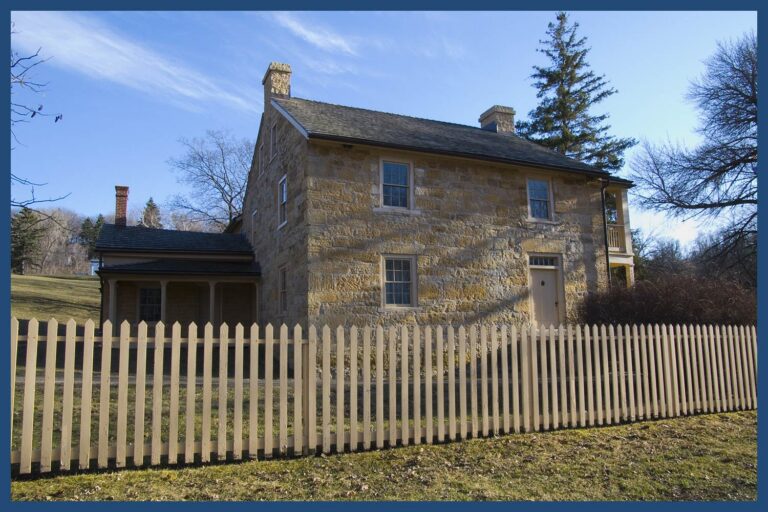

The stewardship of the American Victorian house is a complex intersection of material science, cultural heritage, and modern engineering. In the United States, the impulse to preserve these ornate structures is rarely a simple aesthetic choice; it is a commitment to a high-maintenance, high-utility asset that serves as a non-renewable cultural record. As we move through 2026, the methodology of preservation has shifted from mere “fixing” to a sophisticated regime of conservation, driven by an increasing scarcity of old-growth timber and a maturing market for period-accurate craftsmanship.

To navigate the landscape of historic preservation is to engage with a multi-layered operational blueprint. It involves a transition from standard modern construction logic—which prioritizes speed and synthetic uniformity—toward a philosophy of “breathability,” material compatibility, and reversible interventions. The goal for any steward is to ensure that a structure can exist within a modern context, meeting 21st-century energy codes, without sacrificing the intricate architectural soul that justified its saving in the first place.

This article provides a systemic deconstruction of the premier architectural hubs across the nation. We will examine the technical standards that define high-tier restoration, the economic variables that dictate project feasibility, and the risk management strategies necessary to protect these historical assets. By treating the Victorian home as a living organism rather than a static museum piece, we offer the depth required to distinguish between superficial renovation and authoritative restoration.

Understanding “victorian home restoration destinations usa”

The phrase victorian home restoration destinations usa is frequently utilized by tourism boards to find “pretty” neighborhoods, yet in a professional editorial context, it refers to specific geographical nodes where the “Preservation Density” is high enough to support a specialized labor ecosystem. These are cities and towns where you don’t just find the houses; you find the sash-window specialists, the lime-plaster masons, and the salvage yards required to maintain them.

The Spectrum of Treatment

One must distinguish between the four primary treatments defined by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards: Preservation, Rehabilitation, Restoration, and Reconstruction. “Preservation” focuses on the maintenance of existing historic materials. “Rehabilitation” allows for more significant changes to make the building functional for modern use. Many of the projects in the most famous destinations are successful rehabilitations—modernizing a kitchen while keeping the “gingerbread” trim intact. The misunderstanding often lies in the belief that restoration means “frozen in time.” In reality, the highest form of restoration allows a home to remain a viable residence.

Material Integrity and the “Breathability” Paradox

A primary risk in restoration is the introduction of incompatible modern materials. For example, applying non-breathable acrylic paint or spray-foam insulation to a 19th-century timber frame can trap moisture, leading to “hidden rot” that consumes the structural core. Authoritative restoration destinations are defined by their collective adherence to material science—using lime mortars, linseed-oil paints, and vapor-permeable insulation systems that allow the house to “breathe” as originally designed.

Deep Contextual Background: The Evolution of the American Painted Lady

The American Victorian era (roughly 1837–1901) was not a single style, but a series of overlapping architectural movements fueled by the Industrial Revolution. The expansion of the railroad allowed for the mass production and transport of decorative woodwork—what we now call “gingerbread”—making ornate design available to the growing middle class for the first time.

The Industrial Catalyst

Before the mid-19th century, houses were largely built by local craftsmen using local timber. The Victorian era introduced “Balloon Framing,” which replaced heavy timber joinery with lightweight, standardized lumber connected by nails. This allowed for the complex, asymmetrical footprints, turrets, and bay windows that define the era. The advent of chemical dyes also expanded the color palette, leading to the “Painted Lady” phenomenon where multiple contrasting hues were used to highlight architectural details.

Regional Divergence

The evolution of these homes followed the wealth of the nation. In New England, the styles leaned toward the “Second Empire” with its mansard roofs. In the South, “Italianate” villas featured wide eaves to handle the heat. In the West, particularly San Francisco and Eureka, the “Queen Anne” style reached its most exuberant peak, funded by the gold and lumber booms. These regional hubs became the foundations for today’s premier destinations, as the concentration of these homes forced the development of early preservation laws.

Conceptual Frameworks and Mental Models for Historic Stewardship

To manage or restore a Victorian asset, stewards must employ mental models that differ from standard real estate management.

1. The “Reversibility” Principle

Every modern change made to a historic structure should be reversible. If a modern HVAC system is installed, it should be done in a way that doesn’t destroy original plasterwork or joists. This ensures that future generations can restore the home to its original state if priorities change. This mental model prevents permanent damage to the historic integrity of the destination.

2. The “Sacrificial Layer” Model

In Victorian architecture, certain elements are designed to fail so that others don’t. Paint is a sacrificial layer for wood; mortar is a sacrificial layer for brick. The mental model dictates that you must use a mortar that is “softer” than the brick. If you use modern, hard Portland cement on soft Victorian brick, the brick will shatter during freeze-thaw cycles because it can no longer move.

3. The “Repair Over Replace” Hierarchy

Standard construction logic says it is cheaper to replace a window than to fix it. Preservation logic proves this false. A 100-year-old old-growth heartwood window can be repaired indefinitely. A modern vinyl window has a 15-year lifespan and cannot be repaired when the seal fails. The “top” restoration destinations are those where the local culture values the longevity of the original material over the “convenience” of the replacement.

Key Categories of Victorian Architecture and Strategic Trade-offs

Victorian architecture in the USA is a collection of “Revival” styles. Each presents unique restoration challenges.

| Substyle | Primary Features | Major Restoration Trade-off | Success Signal |

| Gothic Revival | Pointed arches, steep gables | High roof maintenance vs. Iconic silhouette | Original slate or wood shingles |

| Italianate | Low roofs, wide eaves, brackets | Elaborate cornice rot vs. Grandeur | Restored wooden brackets/corbels |

| Second Empire | Mansard roofs, dormers | Complex slate-work vs. Space efficiency | Functioning dormer windows |

| Queen Anne | Turrets, wrap-around porches | Massive painting surface vs. Detail | Multi-color “Technicolor” schemes |

| Stick / Eastlake | Decorative truss work, “Stick” trim | Fragility of exterior wood vs. Texture | Intact vertical/diagonal “sticks” |

Realistic Decision Logic

Stewards must decide between “Period Accuracy” and “Functional Modernity.” If a Queen Anne in Cape May is restored as a museum, it may lack modern insulation. If it is a residence, it needs a 21st-century power grid. The “best” destinations are those where the local community has mastered the “Middle Path”—hiding modern conduits within floor cavities and using discrete high-velocity HVAC systems to avoid drop ceilings.

Detailed Real-World Scenarios

Scenario 1: The San Francisco “Painted Lady”

A homeowner in the Alamo Square district faces a mandated exterior repaint.

-

The Constraint: Strict historic district guidelines require a specific color palette and no synthetic siding.

-

Decision Point: Use modern acrylic paint (longer lasting) or traditional linseed oil paint (historically accurate and easier to strip later).

-

Outcome: The owner chooses linseed oil paint. While it requires more frequent “refreshing,” it never peels in the way acrylic does, preserving the underlying redwood siding for another century.

Scenario 2: The Cape May Coastal Challenge

A Second Empire home in New Jersey faces high salt-air exposure and humidity.

-

The Conflict: Original wood windows are drafty and prone to salt-rot.

-

The Strategy: Instead of replacement, the owner installs interior “invisible” storm windows and applies a marine-grade varnish to the original sashes.

-

Outcome: The home retains its historic profile and gains 90% of the energy efficiency of a modern window at 40% of the cost.

Planning, Cost, and Resource Dynamics (2026 Updated)

Restoration in 2026 is characterized by high labor costs and lower material costs. You are paying for a craftsman’s time rather than a factory’s product.

2026 Range-Based Planning Table (USD)

| Component | Standard Renovation | High-Tier Restoration | Cost Driver |

| Windows (per unit) | $800 – $1,200 | $2,500 – $5,000 | Hand-blown glass; wood species |

| Roofing (per sq) | $500 – $900 | $1,800 – $4,500 | Slate/copper vs. asphalt |

| Masonry (sq ft) | $20 – $40 | $80 – $180 | Lime mortar; hand-carved stone |

| “Gingerbread” Trim | $15 / linear ft | $150 / linear ft | Custom CNC or hand-milled |

Indirect Costs: The “Permit Lag” is a significant factor. In destinations like Savannah or Charleston, getting approval for a specific exterior color or material can take 3–6 months, representing a significant opportunity cost.

Tools, Strategies, and Support Systems

-

Laser Scanning and BIM: Using 3D modeling to document “as-built” conditions before any work starts, ensuring that new structural supports don’t interfere with historic plaster.

-

Petrographic Analysis: Testing original mortar to ensure new mixes are chemically compatible.

-

Historic Tax Credits: Utilizing the 20% federal credit for income-producing properties and various state-level “Easement” programs that provide tax breaks for permanent preservation.

-

Artisan Guilds: Partnering with organizations like the Preservation Trades Network to find master carpenters who understand the “geometry of the turret.”

-

Dendrochronology: Using tree-ring dating to confirm the exact year of construction, which can significantly increase the “Provenance Value” of the asset.

-

Linseed Oil Paint Systems: Reintroducing 19th-century paint technology that penetrates wood rather than sitting on top of it, ending the cycle of peeling paint.

Risk Landscape and Taxonomy of Failure

Preservation risks are often compounding. A single improper cleaning can lead to structural collapse years later.

1. The “Abrasive Cleaning” Failure

Using sandblasting on brick or wood. This removes the “fired” outer shell of the brick or the “hard” summer-wood grain of the timber, causing the soft interior to dissolve in the next rain. This is a common failure in “quick-flip” restorations.

2. Regulatory Risk

Failure to adhere to local historic district guidelines can result in “Stop Work” orders and daily fines. This often stems from a lack of “Preservation Governance”—not having a professional liaison to the local board.

3. The “Museum” Failure

Restoring a house so strictly that it becomes unlivable. If a house cannot be occupied, it cannot be maintained. The most resilient victorian home restoration destinations usa are those where the homes remain vibrant, lived-in residences.

Governance, Maintenance, and Long-Term Adaptation

A historic home requires a “Maintenance Lifecycle” rather than a “Repair Cycle.”

Adjustment Triggers

-

Paint failure: Not an aesthetic issue, but a sign that moisture is trapped behind the siding.

-

Damp basement: Indicates site drainage has shifted; Victorian foundations were designed to stay dry via grading, not waterproof membranes.

-

Mortar dusting: Signifies the mortar is sacrificing itself to save the brick—time to re-point.

Layered Maintenance Checklist

-

Monthly: Inspect gutters; check for pest intrusion in the “soffit” vents.

-

Annual: Professional masonry check; HVAC filter/drain line audit.

-

Decadal: Re-paint siding; inspect roof flashing; check for foundation settlement.

Measurement, Tracking, and Evaluation

How do you evaluate if a project is among the “top” restorations in the USA? It requires looking at lagging indicators.

-

Leading Indicator: The number of original components (windows, trim, plaster) retained versus replaced.

-

Lagging Indicator: The structural stability and energy performance ten years after the intervention.

-

Qualitative Signal: Recognition by local or national preservation societies (e.g., The National Trust).

-

Quantitative Signal: The “Restoration Premium”—the documented increase in resale value compared to “gut-renovated” properties in the same zip code.

Common Misconceptions and Oversimplifications

-

Myth: “Victorian homes are fire traps.” Correction: While they use wood, “Old Growth” timber has a higher density and naturally higher fire resistance than modern “Fast-Growth” pine.

-

Myth: “You can’t have a modern kitchen.” Correction: You can; you just shouldn’t destroy the original floor plan to get it. “Unfitted” kitchens (using furniture-like cabinets) are a popular 2026 trend.

-

Myth: “Older houses are always drafty.” Correction: Drafts are a maintenance failure (failed caulk/weatherstripping), not an architectural one. A restored Victorian with storm windows can be as tight as a new build.

-

Myth: “Preservation means you can’t change the color.” Correction: Historic boards focus on the integrity of the material. Paint is a sacrificial layer and can usually be changed within a historical range.

Conclusion

The preservation of Victorian homes in the United States is an act of intellectual and physical endurance. It requires a rejection of the “disposable” culture of modern construction in favor of a deep respect for material science and historical narrative. To achieve the highest standards in victorian home restoration destinations usa, one must look past the surface-level beauty of a restored façade and evaluate the integrity of the unseen systems. Ultimately, successful restoration is not about stopping time; it is about ensuring that the craft of the past remains a functional, breathing part of the future. The steward of a historic home does not truly own it; they simply maintain it for the next century.